- Reprinted From CoastalOnlineReview.org

The U.S. House last week failed to override President Joe Biden’s recent veto of a resolution that would have rolled back federal clean water regulations, but the future for those rules remains cloudy as the Supreme Court weighs a case that could restrict the Environmental Protection Agency’s authority to regulate ephemeral waters and streams.

House Republicans had sought to reverse the administration’s new waters of the United States, or WOTUS, rule that included regulations that the EPA and Army Corps of Engineers’ reinstated in January. The protections apply to millions of acres of North Carolina wetlands and were repealed by the Trump administration.

NC Decision Makers Voice Concern

The GOP last week fell short of the two-thirds majority required to override Biden’s veto of the resolution sponsored by Water Resources and Environment Subcommittee Chairman Rep. David Rouzer, R-N.C., and Transportation and Infrastructure Committee Chairman Sam Graves, R-Mo.

The 227-196 vote included all seven North Carolina House Republicans and 1st District Democratic Rep. Don Davis voting in favor of the veto override and Democratic Reps. Alma Adams, Kathy Manning, Wiley Nickel, Valerie Foushee and Jeff Jackson opposed. Second District Rep. Deborah Ross, a Democrat, did not vote.

“The Biden Administration’s waters of the United States rule is one of the most damaging in history, with the potential to devastate production agriculture, derail infrastructure projects and harm our economy,” Rouzer, who represents North Carolina’s 7th District, said Tuesday in a press release. “Congress spoke with a loud bipartisan voice and voted against this overreach, but without enough votes from the other side of the aisle to override the President’s veto. We will continue to work to push back against and defang this onerous rule at every available opportunity.”

Rouzer had previously said that rule expands the federal government’s regulatory control, “cloaked under the guise of clean water.”

Stakeholder Groups Weigh-in

Clean water advocates, including the North Carolina Coastal Federation, which publishes Coastal Review, were opposed to the WOTUS rule repeal, saying in 2019 that the rollbacks would “cause significant damage to coastal natural resources and economy” and reverse efforts to protect and enhance thousands of acres of wetlands, hundreds of miles of coastal marshes and thousands of acres of estuarine waters.

Environmental justice groups, such as GreenLatinos, say there has been an ongoing campaign to create confusion around the purpose of the Clean Water Act and who is “burdened by regulations.” The group had urged the April 6 veto that was only Biden’s second.

“With this vote, all present Republicans and some Democrats have aligned with corporate interests and ignored the reality that if we truly value water as a human right, then our waters need to be better protected so that our communities have access to clean, healthy, reliable and affordable water,” GreenLatinos Director of Strategic Initiatives Mariana Del Valle Prieto Cervantes said in a March 29 statement released after the Senate’s 53-43 vote for a resolution of disapproval under the Congressional Review Act, in which a simple majority is sufficient to pass. The House had also voted 227-198 to reject the rule under the Congressional Review Act.

WOTUS Over The Years

The Obama administration finalized the controversial WOTUS rule in 2015, expanding its definition and prompting legal challenges backed by agriculture, construction and coal industries.

The Trump administration replaced the WOTUS rule with the 2020 Navigable Waters Protection Rule, which Biden vowed to repeal via executive order upon taking office.

The Biden administration’s revised WOTUS rule was itself dubbed a compromise that included acknowledgement of recent court decisions and a reversion to some Reagan-era policies.

“The 2023 revised definition of ‘Waters of the United States’ carefully sets the bounds for which bodies of water are protected under the Clean Water Act. It provides clear rules of the road that will help advance infrastructure projects, economic investments, and agricultural activities — all while protecting water quality and public health,” according to Biden’s veto message to the House.

Biden said the loss of a clear WOTUS definition would threaten economic growth, including for agriculture, local economies and downstream communities. He said the veto override would have also negatively affected tens of millions of U.S. households that depend on healthy wetlands and streams.

What’s Next?

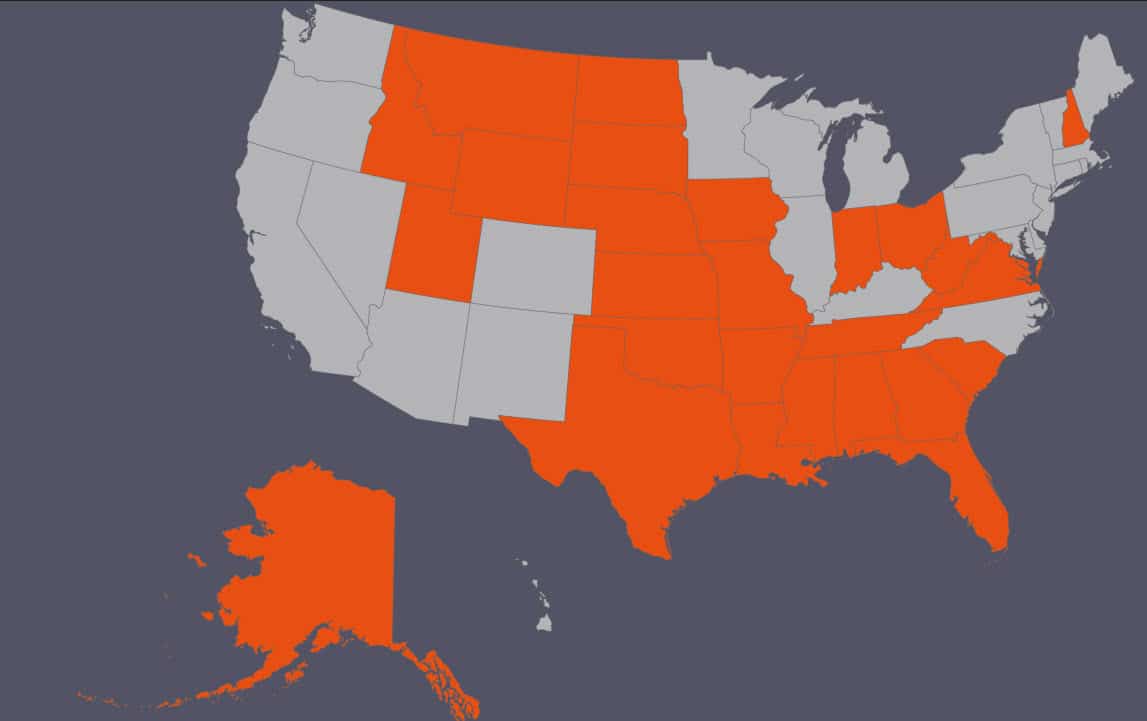

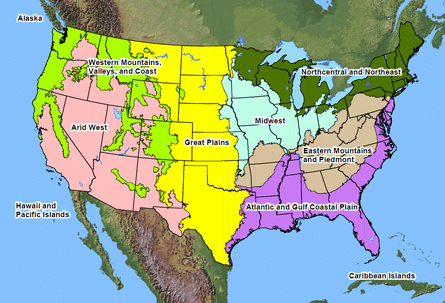

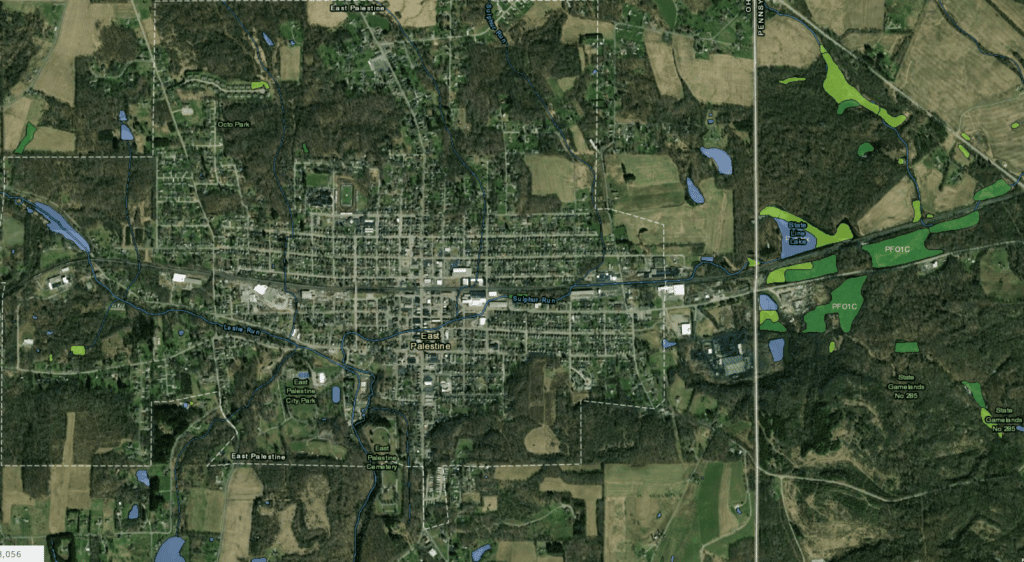

Earlier this month, a federal judge in North Dakota halted implementation of the Biden administration’s WOTUS rule in 24 Republican-led states, Alabama, Alaska, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, New Hampshire, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Utah, Virginia, West Virginia and Wyoming, pending the outcome of a lawsuit. Another recent injunction had blocked implementation in Idaho and Texas.

Elsewhere, the rule took effect March 20.

The Supreme Court is currently considering the case of Sackett v. EPA, to determine whether a federal appeals court set forth the proper test for determining whether wetlands are “waters of the United States” under the Clean Water Act. The case involves an Idaho couple whose home construction violated the Clean Water Act because their lot contains wetlands that qualify as regulated “navigable waters.”