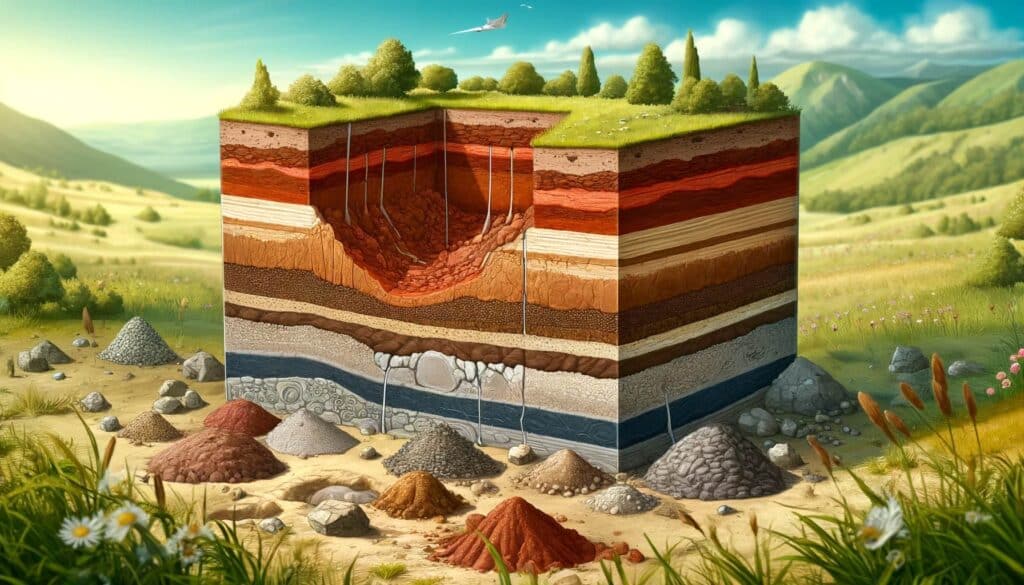

Soil color is more than just an aesthetic attribute; it offers significant insights into the soil’s composition, fertility, and health. Professionals in agriculture, environmental science, and geology rely on precise tools to determine soil characteristics, and one of the most effective tools is the Munsell Soil Color Chart. In this post, we will explore how to use this chart to accurately identify soil color, providing a practical guide for anyone needing to conduct detailed soil analyses.

Understanding the Munsell Soil Color Chart

The Munsell Soil Color Chart is a standardized tool used to determine the color of soil. It is structured around three color attributes: hue (the type of color), value (lightness or darkness), and chroma (color intensity). The chart consists of a series of color chips with coded notations that represent these three attributes, allowing users to match soil samples with high precision.

Equipment Needed

- Munsell Soil Color Chart

- Clean white paper

- A spade or soil auger

- Water (optional, for moistening the soil)

- Natural light conditions (preferably on a cloudy day or in shaded area)

Steps to Identify Soil Color

1. Collecting the Soil Sample

Begin by collecting a fresh soil sample from about 10-20 cm below the surface to avoid weathered or altered topsoil. Use a spade or an auger to extract the soil and place a representative pinch of it on a clean white paper.

2. Preparing the Soil Sample

Crumble the soil gently to remove any clumps and debris. For the most accurate color reading, the soil should be free of organic material like leaves and roots. You can choose to analyze the soil color when it’s dry or after moistening it with a bit of water. Moist soil tends to show the truest color.

3. Using the Munsell Soil Color Chart

Open your Munsell Soil Color Chart and begin comparing your soil sample to the color chips. Start by matching the hue, then adjust for the value, and finally, match the chroma. It’s important to conduct this comparison in natural light, as artificial lighting can distort the color perception.

4. Recording the Color Match

Once you find the closest match, record the notation from the Munsell Chart. This notation consists of the hue (expressed as a fraction or a number), followed by the value and chroma (e.g., 10YR 6/4, where “10YR” is the hue, “6” is the value, and “4” is the chroma). This notation allows you to communicate the soil color accurately in reports or analysis documents.

5. Interpreting the Results

The color of the soil can tell you a lot about its composition. For example, red or orange soil often indicates the presence of iron oxides, while gray soil may suggest organic content or water saturation. Understanding these nuances can help in assessing soil conditions for agricultural purposes, environmental assessments, and more.

Tips for Accurate Soil Color Identification

- Consistent Lighting: Always use natural light for color matching, as artificial sources can alter how colors appear.

- Moist vs. Dry Soil: Note that soil colors can vary significantly between their dry and moist states. It’s useful to assess both conditions if possible.

- Regular Practice: The more you use the Munsell Soil Color Chart, the more proficient you will become in quickly and accurately matching soil colors.

Conclusion

The Munsell Soil Color Chart is an invaluable tool for anyone involved in soil analysis. By following these steps, you can accurately determine the color of the soil, leading to better understanding and management of the land. Whether you’re a farmer assessing soil health, an environmental scientist monitoring restoration projects, or a geologist mapping out a site, mastering the use of this chart enhances your ability to make informed decisions based on the ground beneath your feet.