Reprinted from Coastal Review

They are neither confined to the Carolinas, nor are they bays. That their name is misleading is in many ways very appropriate for the enigmatic formations known as Carolina bays.

But it isn’t what they are that holds the mystery; rather it is how did they get here?

Found in the coastal plains along the Atlantic shoreline, Carolina bays are shallow wetland depressions that are fed by rain or groundwater. They range in size from less than an acre to thousands of acres. Most of the 500,000 or so Carolina Bays are in the Carolinas and Georgia, with the highest concentration found in Bladen County in North Carolina’s southeast coastal plain.

The term “bay” is a nod to the various species of bay trees and shrubs commonly found growing alongside most Carolina bays, but they are also unique reservoirs of many species of carnivorous plants, salamanders, frogs, turtles, birds and mammals.

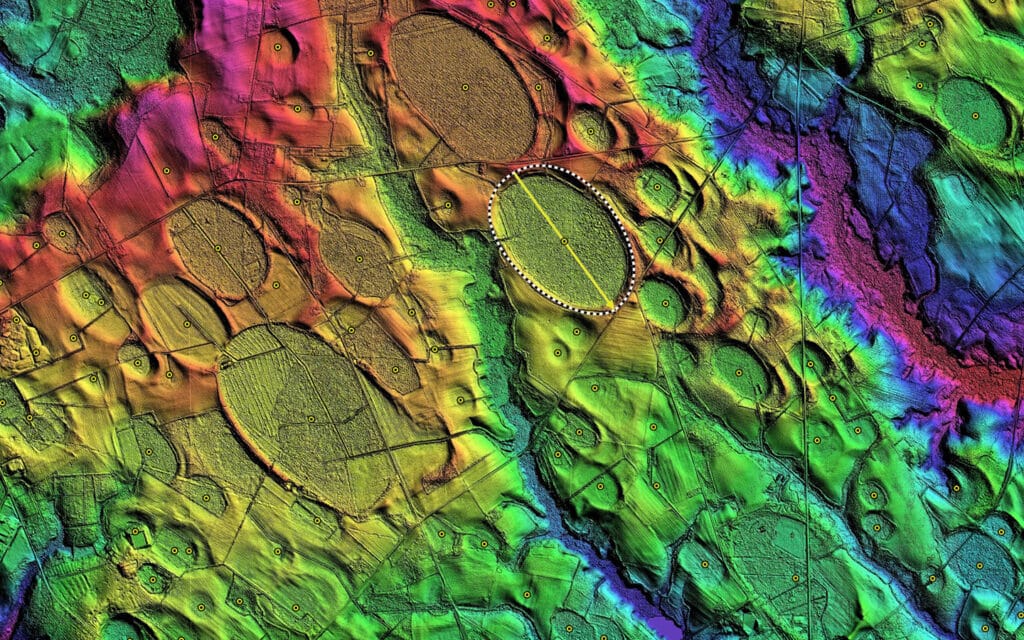

Viewed from the ground they could easily be overlooked. But when viewed from above, Carolina bays create a dramatic imprint on the landscape. They all have a distinct elliptical shape, with a northwest to southeast orientation. They could be described as the crop circles of the wetlands. And oddly, this wouldn’t be their only connection to extraterrestrial theories.

When aerial photography was used to survey farmland in the 1930s surveyors were surprised to see thousands of elliptical depressions across the Eastern Seaboard. Interest in their origin quickly grew, with hypotheses ranging from ocean currents, wind patterns and sinkholes, to meteor showers and prehistoric gigantic beavers.

The mystery of the Carolina bays reached a fever pitch in the 1950s, when a respected University of North Carolina geologist named William Prouty steadfastly contended that the bays were a result of a meteor or comet colliding with the Earth over 12,000 years ago. This idea made quite an impact, so to speak, and debate continued for years about the cosmic nature of Carolina bays. One popular theory links the extinction event known as the Younger Dryas extinction (the same one responsible for wiping out the mammoth) to the formation of Carolina bays, suggesting that the wind and debris created from a comet colliding with the Earth near the Great Lakes region caused the depressions that became the bays.

Exploding comets and mass extinctions make for quite a dramatic birth story. And while everyone enjoys a bit of drama in their tales, doubt about the cosmic creation of Carolina bays led scientists to investigate individual bays more closely. What they found turned out to be a much more earthly creation process.

For instance, if Carolina Bays were the result of a single impact event then they should all be the same age.

“Data negates they [Carolina Bays] were formed at the same time,” said Anthony Rodriguez, associate professor of coastal geology at UNC’s Institute of Marine Sciences in Morehead City.

Rodriguez, along with then-graduate student Matt Waters and UNC associate professor, Michael Piehler, set out to study the origin and evolution of Lake Mattamuskeet, a conglomeration of multiple Carolina Bays in Hyde County on the Albemarle-Pamlico peninsula. Not only did they find no evidence linking these Carolina bays to a cosmic event such as the Younger Dryas extinction, but they also discovered that Lake Mattamuskeet is much younger, by at least 6,000 years, than Carolina bays were assumed to be.

Instead of an icy comet raining onto the Earth, Rodriguez and his colleagues discovered that Lake Mattamuskeet had a fiery beginning. Their analysis of the lake showed that cycles of burning peat associated with dry periods in the climate caused a basin to form where water later accumulated. Winds transported sand and silt, shaping the rim into the characteristic elliptical pattern. And, ta-da, after 1,000 years or so you have a Carolina bay.

When asked about the celestial hypothesis about the origin of Carolina bays, Rodriguez says carefully, “I think in the scientific community it certainly is not believed to be the case. But there is still a subset of believers in a cosmic beginning.”

He has reason to be careful in his response. A web search on Carolina bays brings up multiple sites that provide personal theories touting their cosmic beginnings, interspersed with a limited number of sites detailing the current scientific understanding. It appears that by many, the belief in a cosmic origin is still as passionately supported as it was in the 1950s.

This is not lost of Rodriguez. Parents to similarly aged children, Rodriguez and Piehler were surprised to open their children’s science textbook at a school open house to find that Carolina bays are still being linked to cosmic events.

“On one hand, at least they were in there,” said Rodriguez. “But this just isn’t the case. We couldn’t believe that this is still being told about Carolina bays.”

Still, Rodriguez and his colleagues are cautious to apply the results of their study on Lake Mattamuskeet to explain the origin of other Carolina bays.

“Although we think Lake Mattamuskeet formed by a peat fire, and other bays also might have, they probably aren’t all formed this way,” said Rodriguez.

But he does believe that wind is the driving force in shaping most, if not all, Carolina bays into their characteristic elliptical shape.

“These are soft substrates that shift with wind direction over time. The old timers, from the ‘30s to ‘50s, if you draw a line along the long axis (of the Carolina bays they surveyed) that line shifts a little bit as you move farther south. This goes along with wind direction,” explained Rodriguez.

Despite the growing understanding of the origin of some Carolina bays, the vast majority of them have yet to be closely studied. Rodriguez notes that he has had difficulty receiving funding for additional studies on Carolina bays, causing him to table future research on other sites.

And while some are protected as state or national parks, many of the Carolina Bays are already gone. Over the years, thousands of Carolina Bays have been drained and turned into farmland, recreational spaces, or converted to roadways — erasing these unique geological and ecological formations — and taking the mystery of their origin with them.

Source

Loomis, C. (2013). The Fiery Origins of Carolina Bays. Coastal Review. Retrieved from https://coastalreview.org/2013/08/the-fiery-origins-of-carolina-bays/