The Ivory-Billed Woodpecker, Campephilus principalis, has long been an enigma wrapped in the moss-draped mystery of the southern United States’ bottomland hardwood forests and swamp lands. Once roaming the vastness of the southeastern forests, it was a bird so distinctive and majestic that its presence was deemed a spectacle of the wild. Known for its striking black and white plumage and a bill as white as ivory, it was not only the largest woodpecker in America but also one of the most iconic avian species ever to grace the forests. However, extensive habitat destruction and hunting have led it to the brink of extinction, and possibly beyond.

Natural History and Significance

The Ivory-Billed Woodpecker was an inhabitant of the primeval forests of the Southeast, relying on vast tracts of old-growth woods where dead or dying trees provided the large insect larvae that constituted its primary diet. These woodpeckers played a critical role in the ecosystem, not only as predators that helped control insect populations but also as ecosystem engineers. Their large nesting cavities, excavated in the trunks of ancient trees, became nurseries for their own young and provided shelter for a plethora of other species.

The cultural significance of the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker is multifaceted. It has been a symbol of the wilderness, a muse for bird watchers and naturalists, and a poignant emblem of loss and the consequences of environmental disregard. The bird’s remarkable size and beauty, coupled with its elusiveness, have etched it into the folklore and heart of the American South.

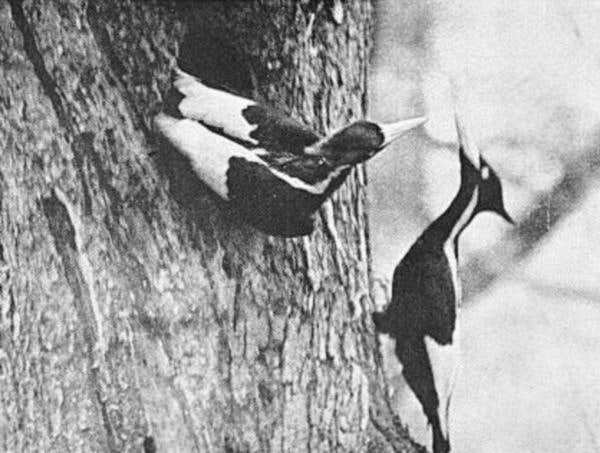

Image by Arthur A. Allen, Courtesy of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

Decline and Presumed Extinction

The decline of the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker was a gradual process accelerated by human actions. The early 20th century was an era of unregulated logging, which decimated the extensive hardwood forests that were the habitat of the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker. These operations did not only reduce the amount of available food but also removed the large, old trees essential for nesting. Furthermore, the bird’s distinctive markings and size made it a target for trophy hunters and collectors, exacerbating its plight.

By the mid-20th century, the species was so rare that it was presumed to be extinct. The last universally accepted sighting was in the 1940s, in the Singer Tract of Louisiana, a large area of old-growth forest that was subsequently logged. The loss of the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker has been a profound one, signaling not only the disappearance of a species but also serving as a harsh reminder of the delicate balance of ecosystems and the far-reaching impact of human activity on the natural world.

Contested Sightings and Conservation Efforts

Over the years, there have been reports and rumors of sightings of the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker, sparking hope that the species may yet cling to existence. The most notable of these was in 2004 when a team of ornithologists from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology reported sightings in the Big Woods region of Arkansas. This announcement triggered a wave of excitement and controversy, as subsequent searches yielded no definitive proof, such as clear photographs or videos, leaving many skeptical.

Despite the lack of conclusive evidence, these reports have fueled a variety of conservation efforts aimed at preserving the habitats that could potentially support a remnant population of the bird. Organizations and government entities have implemented measures to protect large tracts of forestland that could be suitable for the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker, hoping to create a safe haven for these birds if they do indeed still exist. These efforts have also benefited a multitude of other species that share these ecosystems, illustrating a silver lining to the ongoing quest to find the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker.

Reflections on Conservation and the Future

The story of the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker is a poignant narrative that underscores the urgency of conservation. It demonstrates that once a species is pushed to the brink of extinction, the chances of recovery are often slim and fraught with challenges. It also highlights the importance of protecting habitats before they are degraded to the point of being unable to support their native species.

The potential survival of the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker offers a symbol of hope and a call to action. It is a reminder that nature can be resilient if given the chance and that the protection of the environment is an investment in the future of all species, including humans. Whether or not the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker still flits among the shadowed trees of southern swamps, the efforts to save it have ignited a broader conservation movement that continues to grow in importance as we face the ongoing challenges of habitat loss, climate change, and biodiversity decline.

The Ivory-Billed Woodpecker’s legacy is a complex tapestry woven from strands of awe at the natural world, sorrow for what has been lost, and determination to prevent similar fates for other species. The debate over its existence continues to inspire both professional and amateur conservationists to keep searching, keep studying, and most importantly, keep protecting the wild places that remain. Whether it still exists as a living species or has moved beyond the veil into the realm of legend, the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker will forever serve as an icon of the wild and a beacon for conservation. It reminds us of the fragility of life, the consequences of neglect, and the ever-present possibility of redemption through dedicated environmental stewardship.

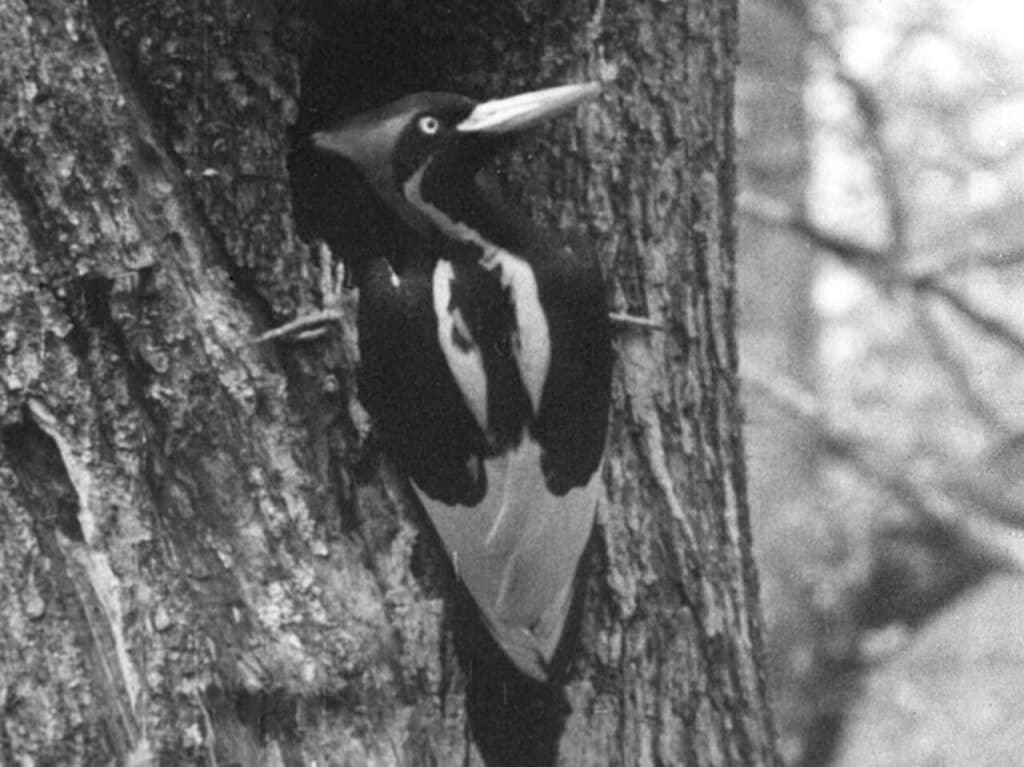

Image by Arthur A. Allen, Courtesy of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology