On August 29, 2023 the US EPA and the US Army Corps of Engineers released a pre-publication version of the conforming amendment to the 2023 definition a Waters of the US. I cannot recall ever having seen a “conforming amendment” in all my years working with this issue. In fact, I am not sure it has ever been done before in any circumstance. I expect the next round of challenges to this rule will focus on this.

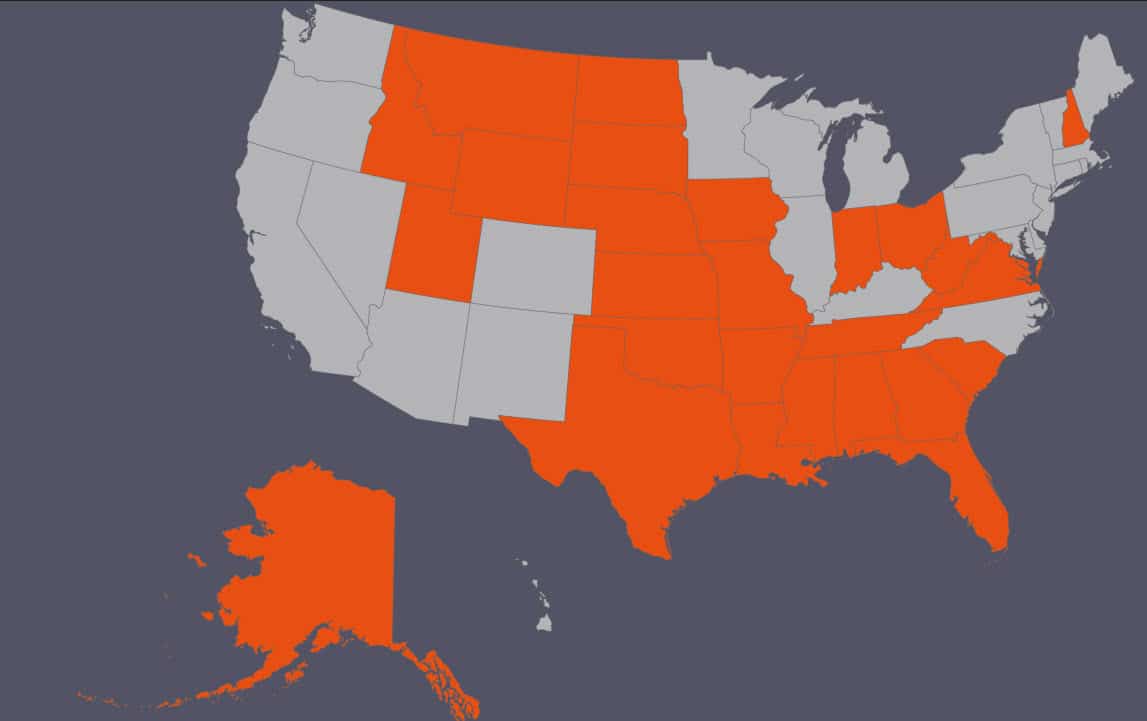

The final version of this rule is the weakest version of the Waters of the US we have ever had. The amount of wetlands no longer covered by Clean Water Act protections is the lowest it has ever been including the Navigable Waters Protection Rule era. It is also important to note that the Supreme Court Decision that prompted this new rule was a unanimous (9-0) one. All nine justices were in agreement despite popular media decrying it was the right side of the bench that dominated the Decision.

This is a final rule and becomes effective on the date it is published in the Federal Register. There is no public comment period. I am still unclear as to why the agencies are in such a hurry to not regulate wetlands.

Much of the new rule discusses why it is proper to issue a conforming amendment without a public comment period. The rule itself is fairly brief, in that it provides the edits to the existing Biden rule. The rule itself does not merge the two rules together into a single document. They leave that up to you. However, we have done this for you and the total new conforming rule follows. We will also be hosting a webinar on this new rule on September 28, 2023. Hope to see you there!

Title 33 —Navigation and Navigable Waters

Chapter II —Corps of Engineers, Department of the Army, Department of Defense

Part 328 —Definition of Waters of the United States

Authority: 33 U.S.C. 1251 et seq.

Source: 51 FR 41250, Nov. 13, 1986, unless otherwise noted.

§ 328.3 Definitions.

For the purpose of this regulation these terms are defined as follows:

(a) Waters of the United States means:

(1) Waters which are:

(i) Currently used, or were used in the past, or may be susceptible to use in interstate or foreign commerce, including all waters which are subject to the ebb and flow of the tide;

(ii) The territorial seas; or

(iii) Interstate waters,

(2) Impoundments of waters otherwise defined as waters of the United States under this definition, other than impoundments of waters identified under paragraph (a)(5) of this section;

(3) Tributaries of waters identified in paragraph (a)(1) or (2) of this section that are relatively permanent, standing or continuously flowing bodies of water;

(4) Wetlands adjacent to the following waters:

(i) Waters identified in paragraph (a)(1) of this section; or

(ii) Relatively permanent, standing or continuously flowing bodies of water identified in paragraph (a)(2) or (a)(3) of this section and with a continuous surface connection to those waters.

(5) Intrastate lakes and ponds not identified in paragraphs (a)(1) through (4) of this section that are relatively permanent, standing or continuously flowing bodies of water with a continuous surface connection to the waters identified in paragraph (a)(1) or (a)(3) of this section.

(b) The following are not “waters of the United States” even where they otherwise meet the terms of paragraphs (a)(2) through (5) of this section:

(1) Waste treatment systems, including treatment ponds or lagoons, designed to meet the requirements of the Clean Water Act;

(2) Prior converted cropland designated by the Secretary of Agriculture. The exclusion would cease upon a change of use, which means that the area is no longer available for the production of agricultural commodities. Notwithstanding the determination of an area’s status as prior converted cropland by any other Federal agency, for the purposes of the Clean Water Act, the final authority regarding Clean Water Act jurisdiction remains with EPA;

(3) Ditches (including roadside ditches) excavated wholly in and draining only dry land and that do not carry a relatively permanent flow of water;

(4) Artificially irrigated areas that would revert to dry land if the irrigation ceased;

(5) Artificial lakes or ponds created by excavating or diking dry land to collect and retain water and which are used exclusively for such purposes as stock watering, irrigation, settling basins, or rice growing;

(6) Artificial reflecting or swimming pools or other small ornamental bodies of water created by excavating or diking dry land to retain water for primarily aesthetic reasons;

(7) Waterfilled depressions created in dry land incidental to construction activity and pits excavated in dry land for the purpose of obtaining fill, sand, or gravel unless and until the construction or excavation operation is abandoned and the resulting body of water meets the definition of waters of the United States; and

(8) Swales and erosional features (e.g., gullies, small washes) characterized by low volume, infrequent, or short duration flow.

(c) In this section, the following definitions apply:

(1) Wetlands means those areas that are inundated or saturated by surface or ground water at a frequency and duration sufficient to support, and that under normal circumstances do support, a prevalence of vegetation typically adapted for life in saturated soil conditions. Wetlands generally include swamps, marshes, bogs, and similar areas.

(2) Adjacent means having a continuous surface connection.

(3) High tide line means the line of intersection of the land with the water’s surface at the maximum height reached by a rising tide. The high tide line may be determined, in the absence of actual data, by a line of oil or scum along shore objects, a more or less continuous deposit of fine shell or debris on the foreshore or berm, other physical markings or characteristics, vegetation lines, tidal gages, or other suitable means that delineate the general height reached by a rising tide. The line encompasses spring high tides and other high tides that occur with periodic frequency but does not include storm surges in which there is a departure from the normal or predicted reach of the tide due to the piling up of water against a coast by strong winds such as those accompanying a hurricane or other intense storm.

(4) Ordinary high water mark means that line on the shore established by the fluctuations of water and indicated by physical characteristics such as clear, natural line impressed on the bank, shelving, changes in the character of soil, destruction of terrestrial vegetation, the presence of litter and debris, or other appropriate means that consider the characteristics of the surrounding areas.

(5) Tidal waters means those waters that rise and fall in a predictable and measurable rhythm or cycle due to the gravitational pulls of the moon and sun. Tidal waters end where the rise and fall of the water surface can no longer be practically measured in a predictable rhythm due to masking by hydrologic, wind, or other effects.